Andreas Felger, Alb Landscape – Permeation, 1974, Ceramic tiles with underglaze painting, 550 x 1000 cm © AFKS

INDOOR POOL, MOESSINGEN

In 1974, Andreas Felger was commissioned to design a mural for the Mössingen indoor swimming pool. The almost forty-year-old textile designer and freelance artist was faced with a task that was not only new to him in terms of the material, but also in terms of its size. Alb Landscape – Permeation consists of 280 painted ceramic tiles, which were specially fired in Höhr-Grenzhausen (near Koblenz) from 50 x 50 cm fireclay tiles. The painting of the many tiles laid out next to each other can be imagined as an oversized jigsaw puzzle, which the artist has put together by constantly alternating between close-up and distanced views.

As ceramic colours lose their luminosity when layers of colour overlap, Felger chose clearly defined areas of colour as well as simple, striking structures and light/dark contrasts that show similarities with the formal principles of his woodcuts and fabric patterns of the early 1970s. The various spatial levels of Alb Landscape – Permeation are layered horizontally: At the lower edge of the picture, the motif is condensed into small sections, above which it opens up to the sky and the striking mountain silhouette. The ceramic painting is patterned in powerful diagonal structures that are positioned at right angles to the grid of the tile joints. The revitalisation of the tile surface through the light reflections of the bath and at the same time the quasi-impressionistic dissolution of the mural in the reflection of the water surface transform the landscape into a dazzling panorama of artistically processed natural beauty.

Author: Marvin Altner

Andreas Felger, Draft for Alb Landscape – Permeation, 1974, Ink on paper © AFKS

Andreas Felger, PAUSA Sculpture, 2015, Wood, blue painted, 350 x 110 x 24 cm © AFKS

The sculpture on Löwensteinplatz points back to the beginnings of the Mössingen textile printing company Pausa in the period after the First World War and at the same time looks forward to the future urban development of the listed building ensemble. Built in the 1950s by the architect and Bauhaus student Manfred Lehmbruck, the Pausa buildings are now primarily used and developed for cultural purposes. Andreas Felger’s biography is closely linked to the history of the former Pausa AG: He worked here from 1950, first as an apprentice, then as a pattern draughtsman, and from 1960 to 1980 he continued as a freelance textile designer. Thirty years later, he returned to his home town as a recognised fine artist.

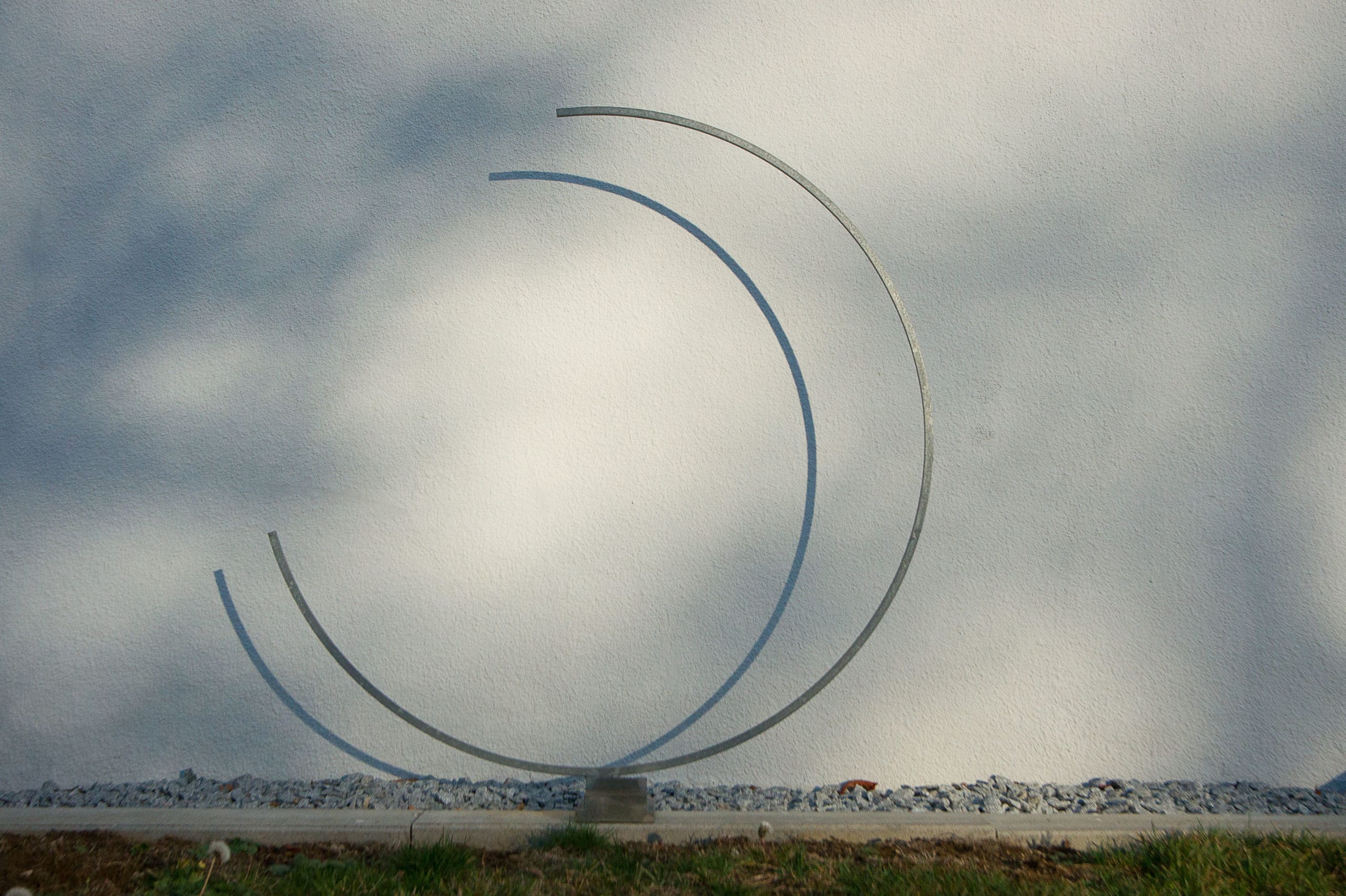

As a sign of his willingness to contribute to the transformation of the historic textile industry site into a place of culture and as its landmark, he donated his Pausa sculpture to the town of Mössingen in 2015. Andreas Felger abstracted the “P” of Pausa, stylised in the post-war period by graphic artist and designer Anton Stankowski into two parallel bars of different lengths for the company logo, into a double “P” consisting of a bar and a circular shape. Back to back and yet standing on its own, the sculpture appears as a contemporary pictogram alluding to the fabric patterns of the golden Pausa years in the 1970s. The circular shape of the Pausa sculpture, with its openness toward the top, allows visitors in the Pausa neighbourhood to look to the future with optimism, without ignoring the history of the town and its textile tradition.

Author: Marvin Altner

Andreas Felger, PAUSA Sculpture (detail), 2015, Wood, blue painted, 350 x 110 x 24 cm © AFKS

Andreas Felger, Encounter – Marketplace, 1995, Oil on wood, 280 x 280 x 5 cm © AFKS

Additional work: Fountain column, 1995, marble, 210 x 32 cm (without illustration)

WOOD RELIEF

Marketplace, Fountain and Encounter are the titles of Andreas Felger’s group of works at the VR Bank eG Steinlach-Wiesaz-Härten in Mössingen, near the artist’s home. The terms describe a forum where people negotiate, where a fountain for money flows (or dries up) and a market for currencies flourishes (or lies dormant). In times of online banking, ATMs and media communication channels, we are experiencing a general acceleration of processes in our everyday lives, including money transfers.

Time also plays a role in the two-part wooden relief Begegnung – Marktplatz (which was initially conceived as a single piece): lines flow, wheels turn, hourglasses refer to a measure of time, transience and the imperative to make the most of the hour. The critical view of time is echoed in the encounter between two abstract figures separated by a snake, a symbol of seduction. Dealing with temptation is an important part of dealing with money and at the same time symbolises a dynamic between people that permeates all areas of life – it is no coincidence that it can be traced back to the relationship between man and woman in the biblical paradise. Does Felger’s depiction perhaps also raise the question of the permanence of the financial market? The small-scale structures in the centre of the picture, the actual marketplace, are hardly anchored in the overall composition, but look more like an ornamented cloth that has been placed in the picture. As such, it could be picked up and carried away at any time.

Bank buildings around the world show us a smooth, reflective, seemingly unshakeable world that is supposed to speak of wealth and happiness. The marble column in the foyer of the bank speaks of such solidity. The coloured relief stands in contrast to this: the natural material of wood, which has been worked with indentations, the intense colourfulness and Felger’s pictorial symbolism relativise the cold beauty of the marble and bring people into focus.

Author: Marvin Altner

CANTICLE OF THE SUN OF ST FRANCIS I–VI (1989)

Andreas Felger’s altar and pulpit paraments set intense colour accents at the places of liturgical events in the bright, high church interior of the Peter-and-Paul-Church in Mössingen. Felger is guided by the I-am-words of Jesus from the Gospel of John and uses colour to mark the celebrations and periods of the church year: I am the bread is the theme of the Trinity season and has green as its primary colour. Purple denotes Advent, the Passion and the days of penance (I am the door), white the feasts of Christ (I am the light) and red Pentecost and the church feasts (I am a king). The abstract lines of Felger’s designs for the fabrics later woven in a Stuttgart based parament workshop are characteristic of his painterly style.

If you make your way from the church to the nearby parish hall, you will discover how elements of different media can merge in Andreas Felger’s work in the wooden reliefs on St Francis’ Canticle of the Sun: Printmaking, textile design, painting and sculpture are interwoven in a variety of ways. At the end of the 1970s, the artist had already begun to work on and paint wooden surfaces, for example the seven reliefs for the Church of the Resurrection in Mainz, which were completed in 1980. The Canticle of the Sun in Mössingen from 1989/90 represents a further step towards three-dimensional sculptural work and is also the first work that he created with acrylic colours. Applied opaquely, acrylic creates a smooth, homogeneous colour materiality, which allows the clear, impressive carved forms to come into their own.

The text by St Francis of Assisi, written around 1225, to which the artist refers, is one of the oldest testimonies of Italian literature, a hymn of praise to God, the Lord, by invoking the four elements of earthly creation as sisters and brothers. An example: “PRAISE BE TO YOU LORD / through brother wind / and air and cloud and weather / which gently or strictly according to your will / guide the beings that are through you”.

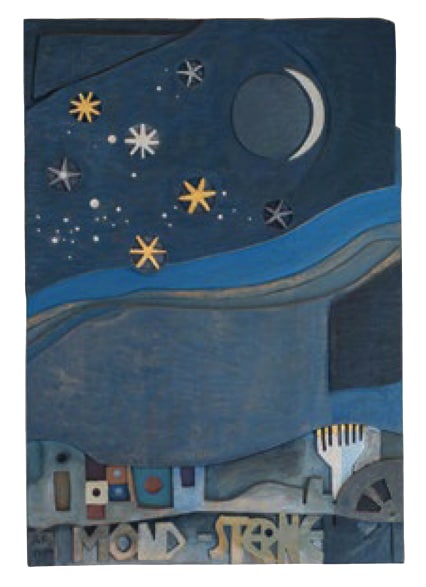

If the ten verses of the chant were arranged side by side, a symmetrical sequence would emerge. In the centre are the four elements air, water, fire and earth, framed by three complementary pairs of figures: Praise of the Lord | Sun | Cosmos | Four Elements | Sorrow/Peace | Death | Praise of the Lord.

So while the two praises of God stand at the beginning and end, the life-giving light and the life-hostile death form a pair of opposites and correspond to the contrasting ideas of cosmic unity on the one hand and human life in the contradiction between earthly suffering and the search for (inner) peace on the other.

If we look at Andreas Felger’s seven relief panels, we see a different, also seven-part sequence: Sun | Cosmos | Air | Water | Fire | Earth | Death. The outer bracket, Sun and Death, have been preserved from the chant (although they have swapped positions). The cosmic and earthly worlds form a pair of opposites. Air and fire are ambivalently connected with each other, inasmuch as both forces preserve (breath/warmth) and destroy (storm/fire). Ultimately, water is at the centre as the source of creation, a metaphor for the divine origin of being.

Andreas Felger, Canticle of the Sun of Francis – Sun, 1989, Acrylic on Lime wood, 100 x 80 x 10 cm © AFKS

Andreas Felger’s Canticle of the Sun, completed in 1990, represents a high point in his work at a time of new beginnings, when he had started oil painting a few years earlier and moved his home and studio from Bad Camberg to Gnadenthal a year later. The panels mediate in a well-balanced way between painting and the spatial layering of the material. Death in the seventh relief is a striking example.

Andreas Felger, Canticle of the Sun of Francis – Death, 1989, Acrylic on Lime wood, 100 x 80 x 10 cm © AFKS

He is not framed by a painted frame, but actually ‘lies’ in a ‘box’ made of the lime wood into which he was cut. The letters TOD crowning it, placed exactly in the width of the coffin, are carved in the opposite direction: The letters protrude beyond the surface, creating a positive/negative effect. The artist often works with separations and overlaps in the reliefs, which not only have formal qualities but also expressive power in terms of content. If Death forms a unity in figure and language, it is superimposed below by the right half of the donkey, which serves as a mediator between death and salvation – patiently bearing its fate and thereby finding the peace that St Francis sings about in the eighth verse: “Blessed are you, my Lord, through those who forgive for the sake of your love / and endure sickness and tribulation / Blessed are those who endure such things in peace / for by you, Most High, they will be crowned”.

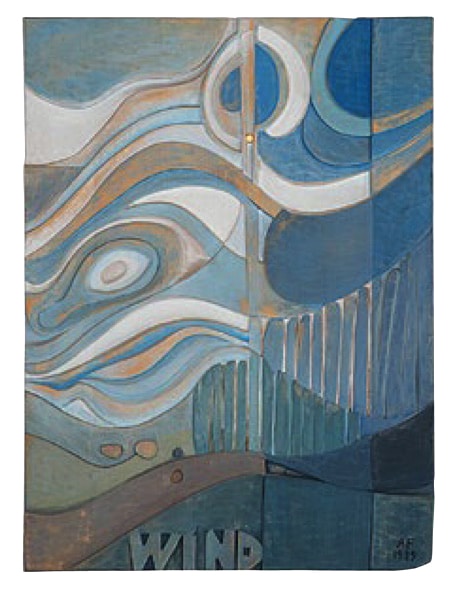

Andreas Felger, Canticle of the Sun of Francis – Wind, 1989, Acrylic on Lime wood, 100 x 80 x 10 cm © AFKS

It is astonishing how Felger succeeds in carving the ease and mobility of the elements of fire, water and air into the wood. The hard material speaks of blazing, flowing and blowing, as if it had been animated by an artist’s hand. The wavy lines of the air in the relief Wind are particularly dynamic, reminiscent of a sketch drawn with vigour. At second glance, it becomes clear that a clear division of the pictorial fields determines the composition and the application of colour: the ground at the lower edge of the picture is stable and dark, the curves on the right are powerfully swelling and the glazes and forms on the left of the dominant pictorial vertical, which can also be read as a figure with extremely moving limbs, are finer and more delicate.

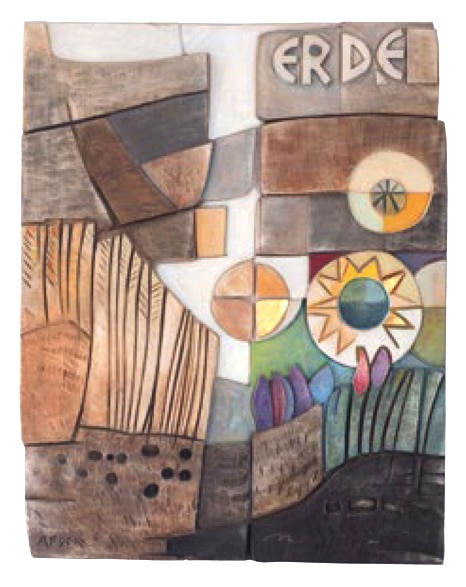

Andreas Felger, Canticle of the Sun of Francis – Earth, 1989, Acrylic on Lime wood, 100 x 80 x 10 cm © AFKS

If you look longer, you will find more and more references within the panels and also between them. The composition of Wind corresponds in several respects to that of Earth. In the centre there is a chalice with a four-part loaf, whose inscribed cross refers to the Christian host, the body of Jesus. It almost seems to the viewer as if the pictorial elements in their simple, soft, flowing forms could instantly be set in motion. The two-dimensional positioning on various levels of depth creates the effect of stage backdrops that have been pushed in front of, next to or into one another. This may also be due to the fact that the reliefs communicate with each other and are interrelated: For example, day and night meet in Sun and Cosmos, while the small seven-branched candelabra in Cosmos refers to the seven-part Canticle of the Sun cycle as a whole.

Author: Marvin Altner

Andreas Felger, Canticle of the Sun of Francis – Cosmos, 1989, Acrylic on Lime wood, 100 x 80 x 10 cm © AFKS

REHABILITATION CLINIC BAD SEBASTIANSWEILER, MÖSSINGEN

SCULPTURE PARK

Andreas Felger has been living in his birthplace of Belsen near Mössingen again since 2009. In 2010, he set up his studio in a former chapel in the spa gardens of the Bad Sebastiansweiler rehabilitation clinic and has been transforming the park into a place of art with his sculptures since 2012. Walking through the park, it is not difficult to recognise the central artistic monument in the Ten Commandments sculpture group. The individual steles, massive, towering blocks of shell limestone, rise up in awe. Only their delicately iridescent surfaces diminish this effect, integrating them materially and aesthetically into the surrounding park nature.

Andreas Felger, The ten commandments, 2013, Kirchheim shell limestone, each 250 x 30 x 30 cm, photo: Benedikt Schweizer © AFKS

It seems as if the ten steles are surrounded by the brightly coloured, seemingly mobile sculptures that Felger has set up in their immediate vicinity: Couple, Fleeing figures, circular form and empty form. They reveal the artist’s light hand, his delight in the figurative, in monochrome, luminous colour, in the metamorphoses of form.

Andreas Felger, Fleeing figures, 2008, blue lacquered steel, 200 x 80 x 0,50 cm, photo: Benedikt Schweizer © AFKS

In figurative terms, the Ten Commandments look like a display of fatherly-creative authority, while the individual sculptures spread across the park look like the world of creatures, animated by an artistic interplay of forms and human-like emotion. A look at Andreas Felger’s work shows that rigour and steadfastness are just as much a part of his art as the spontaneous gesture, the sketched form. Rarely, however, is this closedness expressed as clearly and weightily as in the steles in Bad Sebastiansweiler. The artist is above all strict with himself, in his working attitude. Resulting from consistency and daily practice, it suggests that this spiritual exercise also has a moral dimension. The artist’s actions, at the same time his Craft of Life (Cesare Pavese), are based on rule and regularity. The beautiful, surprising and inspiring about it is that this attitude gives rise to works that appear so radiant and diverse and have so obviously emerged from the moments of action that the plenitude and richness of the – artistic – world opens up. It is only from the regularity of the processes (modelled on the organic) that the freedom of action emerges. This is also a contradiction in the Ten Commandments of the Old Testament, which cannot be resolved theoretically, but only practically.

Andreas Felger, The ten commandments, 2013, Kirchheim shell limestone, each 250 x 30 x 30 cm, photo: Benedikt Schweizer © AFKS

Andreas Felger’s stele geometry stands on an equilateral triangle-shaped foundation that points east like an arrowhead. Although the sculpture is all-visible, it has a west-facing front. This is only noticeable when the viewer approaches the work and recognises the Roman numerals for the numbers I-X. The stele with the number I stands at the averted apex of the triangle from the front, is furthest away from the viewer and is therefore obscured from almost all points of view. The number, which stands for the words of God “I am the Lord, your God”, can only be seen from a hidden position through a gap. The stele labelled III, which refers to the prohibition of images, has a special meaning in this context: “You shall not make for yourself an image of God or any likeness of anything in the heavens above or on the earth beneath or in the water under the earth.” (Ex 20:2-17 EU) The “You shall …” reads like a template for Andreas Felger’s concept of visualisation without representation. The commandments cannot be read, the stelae do not depict them, but they refer to the text and give space to their effectiveness in the immediate vicinity of the former chapel in Bad Sebastiansweiler. In this respect, Felger’s group of stelae is a monument to the Decalogue.

Andreas Felger, The ten commandments, 2013, Kirchheim shell limestone, each 250 x 30 x 30 cm, photo: Benedikt Schweizer © AFKS

As uniform as this monument appears formally, it contradicts our reading habits. Seen from the front, the numbering I-X is reversed to X-I and one ‘reads’ the numbers in the sequence from right to left towards the centre. The fact that it is not shown does not mean that no interpretation is possible: In secular time, Andreas Felger leads the viewer backwards to the commandments because the last four are closest to us, most familiar. They lead to more distant commandments, the creation story, the prohibition of images, monotheism and God’s self-revelation in the first commandment. However, the “guardians” above the park in Bad Sebastiansweiler, whose erection appeals to the upright person in every observer, can also appear quite differently. From a distance, looking back over their shoulders, they merge into a fine light grey surface on which the play of light and shadow of the trees can be seen. The abstract cuboids of the Ten Commandments are receptive to natural phenomena, while the Couple and the Fleeing figures remain completely preoccupied with themselves.

Author: Marvin Altner

Andreas Felger, untitled, ca. 2000, galvanised steel, 130 x 130 cm, photo: Benedikt Schweizer © AFKS